The recent vitriol directed at the Uber-model is unfounded.

This has been a tumultuous few weeks for businesses using the so-called ‘sharing-economy’ or ‘Uber-model’. On the 10th of March, UN Women launched an unprecedented partnership with Uber with the goal to create one million jobs for women by the year 2020. The press release stated that the purpose of the partnership was to work ‘toward a shared vision of equality and women’s empowerment’. Then, eight days later, UN Women cancelled the partnership.

With the announcement of the UN Women-Uber partnership, many businesses using the Uber-model issued a sigh of relief. Finally, there was recognition of the empowerment opportunities which disruptive business models can provide, despite the criticism faced from established business. For Uber, much of this criticism has come from traditional taxi companies or regulatory authorities who have failed to account for new business models eating into their revenue. Other criticism has resulted from a number of highly publicised cases of violence by Uber drivers and of harassment of female Uber drivers by passengers.

The International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITWF) wrote an open letter to UN Women two days after the announcement of the Uber partnership. This letter read, in part: “By classifying drivers as ‘independent contractors’, Uber denies them basic protections, from minimum wage pay to health care and other benefits on the job. Women already make up a high proportion of the precarious workforce, and increasing informal, piecemeal work contributes significantly to women’s economic dis-empowerment and marginalization across the globe.”

It was not only the cancellation of the partnership that took me by surprise, but also the widespread vitriol which followed. This was directed not just at Uber, but at the Uber-model as a whole. I work for a business which employs a derivative of the Uber-model so I have a vested interest in defending the model, but I am also someone who is strongly attuned to the issues of the working class and of intersectional feminism.

The point of this piece is not to defend Uber per se. Uber’s practices have certainly warranted valid criticism in the past. The crux of the issue for me, is the inability to differentiate between business model and business practice. The Uber-model is not any less viable in the face of some poor business practices on the part of Uber and other sharing economy startups. Even so, I feel that the reasoning for the cancellation of the UN Women-Uber partnership was flawed and primarily the result of a failure on the part of the public to critically analyse industry manipulation of public opinion.

I have felt that many industry-wide problems have been laid at Uber’s and the Uber-model’s door without being critically appraised. If Uber fails to perform criminal checks on their drivers, that is a failure of their practices, not their model. As despicable as the rape and harassment cases have been against Uber drivers, the transparency which the model allows has resulted in the swift capture and prosecution of the offending parties. It would also be naive to think that this transparency does not diminish the number of cases of sexual harassment and rape when compared to the traditional and informal taxi sector (where drivers and their passengers are anonymous). The enhanced safety factor is actually one of the primary reasons for Uber’s success in places such as Cape Town and Johannesburg.

Another claim levelled against Uber is the exploitation of low-skilled individuals. This claim also suffers from the same faulty premise that this is somehow especially true for Uber and that somehow the Uber-model leads to exploitation. If one critically examines this claim, it very easily falls apart. Uber and other sharing platforms have to offer an adequate value proposition for service providers to stay with their platform. If they do not, drivers or service providers will eventually join other platforms or taxi companies. They provide agency to those who are often exploited by traditional corporations. They provide work to those who have been disenfranchised by the current economy. How then is exploitation inherent in the model?

I am also highly sceptical of the claims contained within the open letter by ITWF. Many companies adopting the Uber-model differentiate themselves on service not price. This implies then that Uber has to ensure that their hourly rates are above minimum wage, and significantly above if they expect their drivers to maintain a suitable quality of service. Other informal taxi services lack any of these protections and while traditional taxi companies may have been paying above minimum wage, I doubt many of them provide benefits. This once again raises the question of why Uber-model companies are being called out for the lack of benefits. No jobs I have held as a graduate have offered me benefits. My partner is a teacher at a government school and although she has a pension contribution, she is also not provided with medical benefits. How then are these specific problems of the sharing economy?

Finally, I reject that the Uber-model disempowers women or their drivers in general. For the first time, many women are able to hold jobs which may be strongly against the industry norm. Many of the ‘share-workers’ I have interacted with and read about appear to be incredibly empowered. Low level workers finally have agency. They have no middle management to deal with and the pay structure is transparent. Part-time workers are able to find additional work to supplement their income. A mother is now able to find employment which fits around her schedule with her kids. Workers are no longer confined to a single occupation and many have claimed to be stimulated by the ability to work across industries. This really does not sound like disempowerment to me.

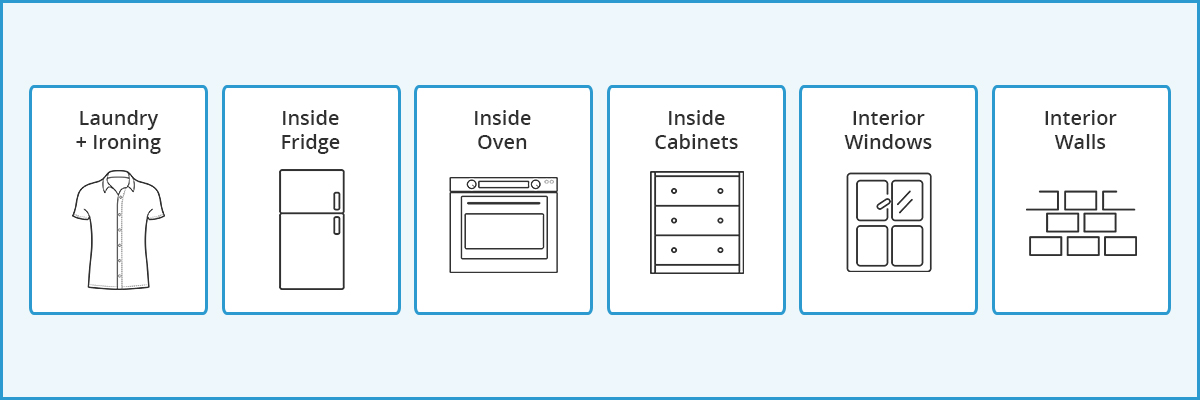

I work for SweepSouth. We provide a platform for cleaning professionals to access clients. We are bringing professionalism to the domestic cleaning industry, which is traditionally dogged by exploitation and role asymmetry. We are intent on destroying the madam-maid mentality which is commonplace in South Africa. We do this both in the language we use and in providing agency for our cleaning professionals. If they do not want to work with a specific client, they don’t have to. Hate dogs and cats? You don’t have to deal with them. Worried about toxic cleaning products? SweepSouth offers eco-friendly, non-toxic, hypoallergenic cleaning products. Furthermore, cleaners tell us which days they would like to work, which provides flexibility in the face of other family commitments.

After cleaning jobs, SweepSouth clients are rated by domestic cleaners and vice versa. Therefore, instead of cleaners having to put up with a bad client, the cleaner knows that she can refuse a job and will easily have access to other work. SweepSouth cleaners are paid an hourly rate of three times over minimum wage and clients have their card details validated beforehand so as to prevent withholding of payment for work done and as an additional safety measure for cleaners. All SweepSouth cleaning professionals are insured while working at clients’ homes. In the past, a breakage might result in a loss of employment or the docking of wages.

The reason I joined SweepSouth is because of the opportunity we offer unemployed black women, who are so frequently exploited and marginalised in South Africa. SweepSouth domestic cleaners very quickly reach a steady monthly income which is above the industry average. They are allowed to deactivate from our platform whenever they like in case they have personal issues to deal with, knowing that they can easily return to the platform instead of having to restart the process of looking for work. These are our practices. Not our model.

There are certainly things which we cannot provide which larger corporations can, but very few of South Africa’s 1.2 million registered domestic workers worked for any sort of corporation or agency before joining our platform. We hope to provide extra cover for SweepSouth cleaners as well as an educational fund for their children when our platform is able to generate enough profit to sustain these programmes. In the mean time, we offer a living to some of the hardest working women in this country. The only thing that makes me sad in my job is the fact that I cannot provide work opportunities to more of them.

Operations Manager

SweepSouth

2 thoughts on “Don’t judge the model, judge the practice”

Comments are closed.